Navy Nagar Parade Ground Sea Wall

Colaba, Mumbai, India

Present Day

—————-

Sunsets are beautiful, long drawn out affairs in India. The Almighty may have overlooked giving us mineral wealth, but sunsets over the sea? Boy, has he been more than generous with them. This evening outdid other evenings in sheer splendour. A red and orange glow set the western horizon on fire.

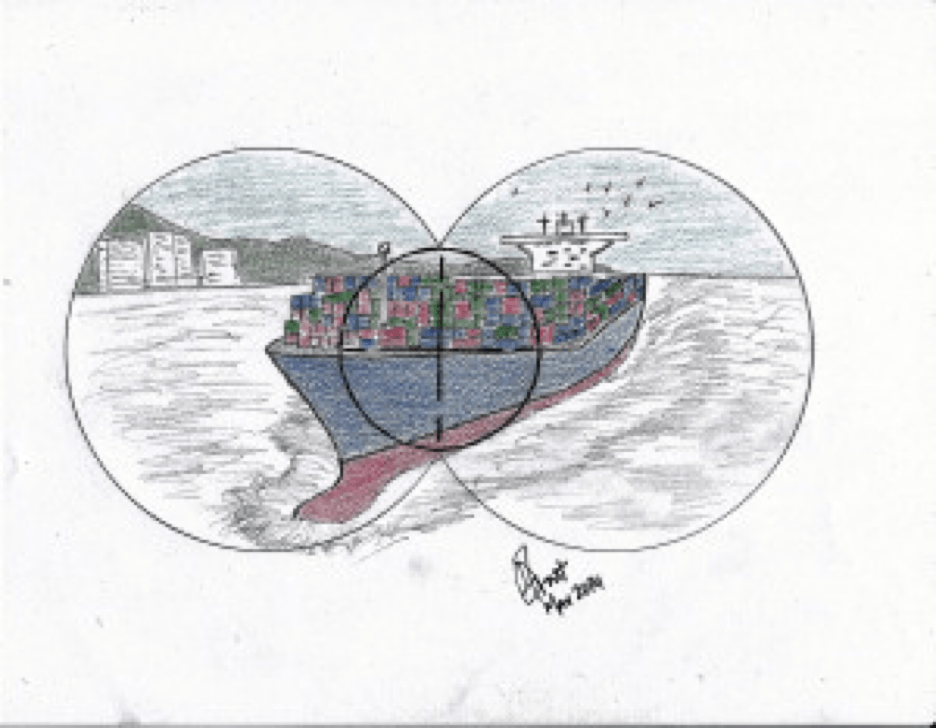

The Japanese container ship I had been following was barely visible now against the afterglow of the sunset. The Amaretsu Maru. I had read the name off the hull with my Oberwerk Ultra. The Oberwerk is mid-range stuff, still way above anything you might find off the shelf at Walmart. It is crystal clear at 5000 meters and the Back Bay is only 3.5 kms wide. The night vision is a bit grainy but still good if you know what you are looking for.

I couldn’t afford a Kowa. I used to pack one though, when I was Lt Commander on the Sindhudhanush. The Kowa could grab star light and enhance the image resolution, making the it seem like you were viewing something that was sitting right next to you in broad daylight. For my current hobby though, which happens to be ship gazing, the Oberwerk was doing just fine.

Twenty minutes prior, the Amaretsu had passed within ten cables of the sea wall on which I was perched (a cable is a nautical unit of distance and roughly equivalent to 185 meters). As I zoomed in on the vessel, I discerned around five or six tiny figures, crew members, leaning against the rail, amidships, dwarfed by the mountain of neatly stacked, multi-colored containers behind them. P&O NedLloyd, Hapag Lloyd, Maersk, COSCO; the containers were a jumble of brand names garishly painted over their rust-colored bases.

I wondered what the seamen were doing, standing there idly. In the Navy where I had been, there was no such thing as an idle seaman. Perhaps they were just taking a breather, after the extreme exhaustion of setting sail. Or perhaps they were catching the last sight of land for the next several months.

I know how that feels, the melancholy that sweeps through you when you watch people scurrying like tiny ants, around the wharf. You cling on till the very last minute, before the coastline disappears completely.

The Dhanush’s range had been virtually infinite. A nuclear powered sub is limited only by the periodic need for provisioning (food supplies, etc). Leaving shore in a sub is like severing an umbilical cord.

Maybe the guys at the rail were watching me and saying to each other,’ Will you just look at that lucky bastard now?’ But then, maybe they were just standing there and taking a long pee. I used to do that when I was on watch as a sub-lieutenant on the Nilgiri. Standing precariously over the raised parapet on which the stern rail was mounted, I would let loose and watch the stream disappear into the churning wake, turning the sea infinitesimally more acidic. Leonardo di Caprio would have done the pretty much the same thing at the bow rail, had Kate Winslet jumped before he arrived, I thought with a chuckle.

Amaretsu literally means ‘of the heavens’, an interesting name for an ocean-going vessel to have, I thought to myself, as I leaned back on my splayed palms on the concrete seawall. I was sitting facing the surf, my legs dangling over those oddly bulging star-shaped concrete blocks that were haphazardly placed in the sand, to break up the waves. The Colaba seawall was where I came and sat after I had my jog. I would sit there catching my breath, dripping sweat all over the concrete, letting the cool sea breeze hit me like a shock wave. Till six months back, I had company. Shanta. She came along most days, when she felt a bit better.

I ran while Shanta walked. Reaching way ahead of her, I would be sitting on the sea wall parapet long before she came trudging slowly up. We would sit on the concrete parapet and pass the Oberwerk back and forth between us. When it was my turn, I watched the ships and when she had the binoculars, she followed the gulls and the fishing skiffs. When we got bored looking, Shanta would take out some chutney sandwiches and we munched quietly, our arms round each other, like lovers on Marine Drive.

Sometimes, Shanta wanted to play ‘what’s the good word’. We would sit there thinking up words that only we recognized. We played the final game two days before Shanta went into Jaslok for the last time. It had been her turn to think of a word and she thought of ‘heaven’. I lost that turn, even after she kept bombarding me with a rush of clues, over and beyond the maximum three permitted. The last one had been an exasperated, ” Okay, you old mutt, it’s a place we’ll both go live in and have a ball, at some point in time. “

The Amaretsu Maru was a very large vessel. I figured it probably shoved aside a hundred thousand tons of the Arabian Sea as it battered and bludgeoned its way forward. And now it was gone, blended in with the dusk, swallowed up like Shanta, over the edge.

Off to the south-east, across the Back Bay, the Nhava Sheva Terminal of the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust, was ablaze with lights now, looking like some alien space port from a Ridley Scott sci-fi picture.

There used to be a time when lights were an ominous sight………..

———————————-

Navy Nagar Parade Ground Sea Wall

Wednesday 26th November, 2008 (19.00hrs)

As the tide sneaks in, I note that the sea has suddenly grown calmer. The waves that had been crashing on those star-shaped blocks below, are now jostling each other playfully. The horizon has darkened.

As if on cue, the vendors, their pushcarts, the pony rides and the balloons, have melted away into the lights of the city. It’s almost a sudden transformation. One minute the tiny beach is teeming and the next, it is desolate, ceding territory to the tide, if only for a short while.

Phosphorescent foam begins washing over the rocks, making them glitter. The sky had been overcast all evening and now suddenly even the winds are still. Had Wagner been here he would be writing a crescendo for the scene. The world seems to stand still. I usually don’t stay this late but today is special.

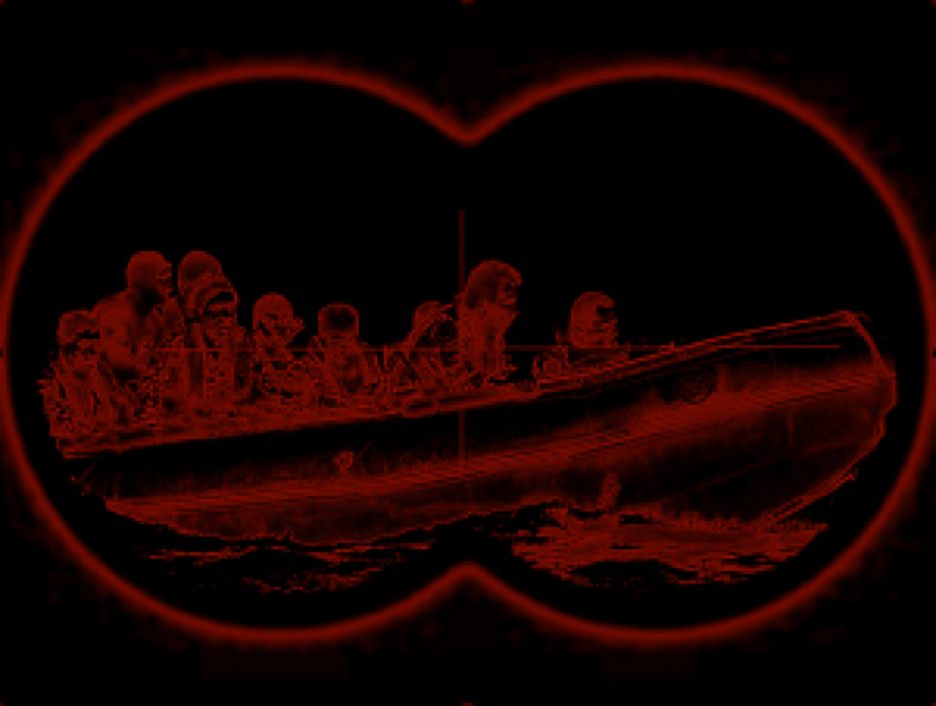

A light catches my eye. It had blinked on briefly some way beyond the surf, making me bring up the Oberwerk and train it in the general direction of the flash. Immediately the two speeding zodiacs fill my eyepiece. There are five of them in each, huddled forms, outlined in an eerie red glow by the night vision of the Oberwerk. Each man seems to be toting a bulky backpack. The two inflatables pitch and bounce on the waves, releasing bursts of spray as they hit the troughs and the crests, racing toward the little strip of sand that borders the jumble of the star-shaped blocks by the seawall. On their heading they’ll be beaching right about a hundred meters from where I am perched.

My conversation with Jimmy at the Navy Club last evening flashed back instantly. Commodore Jimmy Taraporewala, NDA roommate. Jimmy had on an overall that the members of his corps wear, with those shoulder patches depicting in graphic red and black, a crocodile lashing out with its tail. It was an insignia I was intimately familiar with, having worn it myself for six eventful years at MARCOS.

We were both nursing sodas, except that mine had a couple of fingers of McDovell Premium in it. Not needing much coaxing, Jimmy whispered, “We have a red alert, Krish. Something is about to happen.”

I looked up sharply, “Another landing?”

Jimmy nodded and then grimaced. “Those assholes at the IB have no clue. No news from our assets at the ISI. JCB and DNI are working on it non-stop. All Coast Guard vessels, as well as the Sindhukirti and Sindhuratna, have slipped their moorings. The Talwar and Trishul are on their way from the Maldives. We ourselves are at 5 minute readiness. But how can anyone patrol a two thousand mile coastline?”

I leaned forward, “Where did the tip-off originate?”

“The British GCHQ.” Jimmy stared at me and nodded, “ Of late, there has been more exchanges between us than you had in your time, Krish.”

“What about those Neptunes you just acquired? We have two now, don’t we? Put them on a permanent orbit over the west coast till this thing is over.” I was referring to the new Boeing P-8I Neptune reconnaissance aircraft that have just been inducted into the Navy.

“Boeing technicians are still sorting out some glitches with the Magnetic Anomaly Detectors in them,” Jimmy made a disgusted face and the conversation veered away to his son, Ronnie, who was passing out of the NDA in a week.

———————-

Back at the seawall, premonition made the hair at the nape of my neck stand rigid. I peered through the Oberwerk, at the huddled shapes on the zodiacs. Fishermen aren’t out so late and besides, they don’t gallivant around the Arabian Sea in zodiacs, I said to myself. They might have seen me, silhouetted against the street lights behind. I crossed my legs over the parapet, stowed the Oberwerk into my windcheater and quickly dropped down to the ground on all fours and began picking my way through the rubble on the side of the road in a crouching gait, in order to remain below the level of the parapet.

10 yards of knee-lacerating crawl brought me to a crack in the seawall where the cement had crumbled, forming a gap large enough to let a man through. It had probably been deliberately created just to have a short-cut to the asphalt, by those street urchins who beg around the beach during the day. I slid through the gap and started slithering down toward the sand, gingerly stepping over the star-shaped blocks, knowing they would be coated with moss and slippery as hell.

As I placed my foot in the squishy sand, I saw the silhouettes. The men had by now, run the boats onto the sand and begun getting out of their polyurethane suits. They seemed to be speaking and gesturing with each other but the steady shush of the waves drowned all sounds around. The one who was already out of his wetsuit and still bare-chested, was the first to sense my presence. In a single fluid motion, his right hand came up holding a handgun while he dropped to a crouch.

I had expected that. I raised my hand, palm outward and whispered,” Salaam, Bhaijan.” (Greetings to you, brother). He peeled off from the rest and came forward. The gun in his hand was a 9mm Luger and he brought it down, holding it loosely in his right hand, as he came to a halt a few feet from me. He was clean-shaven, diminutive and wiry and had piercing bright eyes that had no fear in them. A pro.

“Salaam,” said the man,” Do you have our stuff, janab?”

I nodded,” Its all in there.” I gestured toward the star-shaped blocks by the seawall.

“Aapki tareef?” (Who are you?), he looked up at me.

“Aftab”, I said, to which he nodded.

“Aur aap hain, janab…?” (And you?)

He turned his piercing gaze at me and said, “Babar”.

“Leh, usko samhal, Ajmal, “ the man named Babar barked and a wild-eyed guy who looked young enough to be a teenager, dropped what he was doing and made his way toward the blocks. I braced myself. The star shaped blocks were about 100 meters from where we were standing. The boy, Ajmal, would be gone maybe five minutes max. They had five minutes to realize I was lying. There was nothing there.

We waited, my hands on my waist, my right palm just inches away from the Glock34 that I always carried with me these days. Ex-special forces members are licensed to carry a hidden automatic weapon. The Glock had become a part of me, nestled in the small of my back, now hidden by the windcheater.

As the seconds ticked away, the man called Babar said,” Rana ne wapsi ki koi zikar kiya? (Did Rana mention the extraction plans?)”

“Rana?” I stared at the man, “Nahin, hamein Rana ne nahin bheja.” (Rana? I have no idea. Rana didn’t send me)

“To phir?” I could see the first flush of puzzlement in the man’s eyes, as the man called Babar straightened up and stared, “Kisney bheja?” (Then who sent you?)

“MARCOS,” the acronym, pronounced clearly, hung in the air for a split second. I had whispered it so softly that only Babar heard me.

Maybe it was fatigue brought on by the 50km ride on the zodiacs or the stress that any clandestine operation can bring on, I don’t know. But a split second can be a very long time in our business. Time enough to die.

The man called Babar was bringing his firing arm up when the Glock appeared almost by magic in my hand. It took another half millisecond for Babar to grow a third nipple, right between the other two. He collapsed in a heap and rolled over, staring up, squinting, his eyes trying to focus. Perhaps he had noticed a new star on the belt of Orion. A trickle of blood began seeping out of the corner of his lips and his nostrils, pulsating in step with the frantic thrashing of his dying heart.

Instantly the confined space in the beach was filled with the klicks and coughs of silenced automatic weapons erupting lethal fire. My forever faithful Glock did a lot of talking tonight. One of my rounds opened up the kid, Ajmal’s head like a melon. He kept walking a while, his body still believing it had a head, before it realized it didn’t and collapsed.

I dispatched the rest quite easily. These were dumb kids, just a bunch of miserable suckers, out for twisted glory. The last two dropped their weapons and tried to run into the waters. Maybe they wanted to swim all the way back to Karachi. They never had a chance. When you are up against the MARCOS, you never have a chance. We are trained to shoot by sense alone, in the dark. I picked them off pretty easily. Looking around at the carnage, I speed-dialed Jimmy.

As I proceeded to pick my way back up those rocks, I heard a groan. I turned to see the man named Babar and I walked over to him. The spit of sand around me had turned into a slaughterhouse. Babar’s chest heaved as he made an effort to speak and I brought my face closer. If he had any last words, I was curious to find out what they were.

Alas, the man named Babar disappointed me. He just uttered one word,” Gaddar” (traitor). His eyes gradually began taking on the glazed sightlessness of the dead and I decided to hurry him along. I brought my Glock up and pressed it against his forehead.

Before pressing up on the trigger I grinned. I wanted him to see me grin. And then I spoke clearly so the words would register in his dimming brain,” Here’s one for your janab Hafeez Sayeed, asshole.”

I had climbed back up onto the asphalt and was leaning against the parapet of the seawall when I heard the first wails of the sirens and the lights charging up Pilot Bundar Road.