A month or so after Shanta passed on, in May of 1969, I began going out with the Culvers for breakfast every morning at the Tim Hortons, the one down by the ESSO pump, on Sherbrooke West and Grand.

I’m referring to Irv and Sally Culver, retirees like me, living on the same floor, down the corridor, by the fire escape.

At first they felt I was lonesome and needed company and that’s why they invited me to join them at Tim Horton’s for turkey bacon sandwiches one morning, early July 1969. They must have liked the experience because they insisted on having me around everyday thereafter. I felt comfortable with them and came to enjoy those outings.

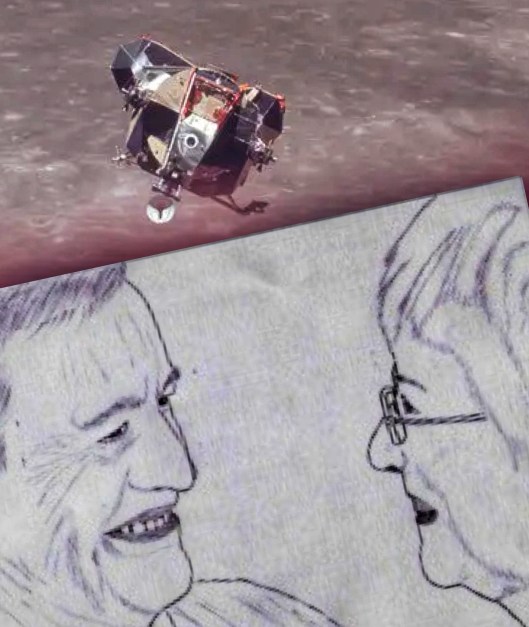

I remember the morning of July 20th, 1969. Irv, Sally and I were talking animatedly about the moon landing the day before. The live broadcast had been phenomenal. In fact I am sure that everyone else in the cafe was wrapped up in it too.

“Did you watch Neil Armstrong’s little speech? One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind?” That was Irv.

“Of course. Very apt, wasn’t it?” My interest perked up.

“Sally says Armstrong actually said ‘one small step for a man’ but I clearly remember him saying ‘one small step for man’. Sally rolled her eyes at that and I couldn’t help thinking how lovely she still looked, even at 52.

“Interesting, how an article can twist the whole meaning of a sentence. Did you know him, Irv? Neil Armstrong?”

Almost all his working life, Irv Culver had been at Lockheed’s Skunk Works, as a part of the team that developed what would come to be known as the SR-71 Blackbird. In later years, the Skunk Works developed such legendary flying machines like the freakily angular F117 Nighthawk, the F22 Raptor and the F35 Lightning.

At the mention of Neil Armstrong, Irv perked up, “Not personally, but I’d seen Armstrong a few times over the years. The first time was when he was visiting the Skunk Works, this must have been around 1962, maybe ‘63. He was a member of the ‘new nine’ group of astronauts, invited to take a look at the new YF-12A prototype, the fore-runner of the SR-71 Blackbird. We had tested out the TEB igniter on the JP-7 fuel inside the lab and were going to have a test flight that day. Things were pretty antsy around the huge shed. JP-7 burns only at elevated temperatures and is therefore quite safe to have lying around, but TEB ignites on contact with air. And without TEB injected into it, JP-7 wasn’t going to light up.”

Sally and I exchanged glances and smiled. Irv was in his elements and unstoppable now, “While the others in the group of astronauts spoke only with our Chief Engineer, Kelly Johnson, Armstrong made it a point to go around, stopping by every member of the Skunk Works team and even the Pratt and Whitney guys working on the J-58 power plant. He listened attentively to each one of us. My last glimpse was of him shaking hands with a contractor’s man who was holding a ladder while another changed a light bulb.”

I was primed by now and bristling with questions. “Wait, don’t move, I’m going to get us some more coffee and you’re going to tell me more.” I hurried back holding three mugs and I was firing away as I placed them on the table,” How did the Skunk Works get that name?”

“Well, when we started, back in ’43, it was in a converted circus tent as there was no other space within the Lockheed facility. And we happened to be right next to a plant producing manure, its odor permeating our tent. When my phone rang one day, I jokingly said,” Skunk Works inside man, Culver speaking.” The name caught on right away. Since then, the term “skunk works” has been widely used to describe a group, within an organization, given a high degree of autonomy and unhampered by bureaucracy, tasked with working on advanced or secret projects.”

Irv and Sally had an engagement that day and had to leave and so my curiosity had to wait till the next breakfast.

——————-

A year slipped by, 365 blissful days of walks, breakfasts and stimulating conversation with the Culvers. Shanta would have loved these two.

I reckon it was around that time that Irv began fading away. Gradually. Right before our eyes. It began with him not being able to locate the car keys. Another time, he got lost coming back from the pharmacy and someone saw him wandering listlessly around and called 911 and a cop arrived and drove him home.

Alzheimer’s crept up on Irvin Culver steadily for the next nine years. Until one particularly frigid December night in 1980, when he quietly died in his sleep at the Montreal General. Of course, one doesn’t die of Alzheimer’s. One just fades away. Irv actually succumbed to colon cancer. Sally had always pestered him to eat more greens but he never listened. Anyway, for Sally, Irv’s passing was more like the grand finale of a painful nine year long goodbye.

——————–

After Irv, Sally and I would see each other at least once every day. We would accompany one another to our doctors’ appointments. I had a painful knee condition that got aggravated in the cold. Sally was trying to keep her cholesterol and BP down. I had no living relatives in Canada and Sally’s only daughter, Cora, lived somewhere on the west coast. Therefore, for the most part, we had just each other. While we couldn’t bring ourselves to enter the Tim Hortons again, we had our daily walks down Sherbrooke.

Some days we took the pedestrian path up to the Westmount Library where we sat for an hour catching our breath and browsing through the journals. I loved the National Geographic and I loved watching Sally peer through her bifocals into the People Magazine or Vanity Fair.

Sometimes we ambled west, toward the Montreal West train station. We’d flop down on the benches by the tracks and watch the ebb and flow of the commuters. Once in a while, a long distance freight train thundered by. We’d sit a while and then make our way back, stopping at the Pharmaprix, right across from our apartment block, to pick up a prescription or maybe a toilet paper roll or something.

We would then trudge back. To our separate little worlds.

I don’t know when it first happened but it gradually seemed natural that we held hands as we walked.

————————-

I don’t remember too good these days but I think it was the Christmas Eve of 1985. Cora had written that she wouldn’t be able to make it, so for Sally and me, it was like any other day. Except for the daily Christmas carol bombardment on TV and radio. She didn’t want to go for the mass at St Joseph’s this time. Said she was tired. We went for a walk, a shorter one, up Cavendish and back. As I said before, my knees didn’t like the Canadian winter. Sally too had grown gaunt, with all her food restrictions. So, while the whole city seemed to explode in merriment, we were back, waiting, while the elevator took us up to the 14th floor.

The ritual thereafter began predictably. Like hundreds of other evenings. Me, giving Sally a quick peck on the cheek at her door and walking down the length of the hallway to my apartment. And her, waiting till I reached my doorstep and giving me a tiny wave. Only this time, she wouldn’t let go of my hand. She slid her arms through mine and pressed up against me. “Don’t go…stay….please.” Her voice was a whisper.

Afterward, we lay in the dark, our faces inches away, lazily giving each other tiny kisses all over. My head felt heavy, like all this was a dream.

The Christmas eve excitement was ramping up outside our tiny oasis as we lay back and listened to the sounds coming from the corridor outside. Squeals of delight, hurrying footsteps, the pitter patter of kids running ahead, to catch the elevator. Across from us, a mother was shutting her front door with,” Nicholas, did you remember to take your mittens?” A door opened somewhere and sudden slurred shouts of welcome erupted and then muted as it slammed shut.

When I turned to look at Sally, she was asleep, a smile still playing on her lips, like some supernova remnant. “Goodnight, darling,” I whispered and held her close till I drifted off.

Sally moved in with me the next day, Christmas Day and surrendered her lease within a month. It seemed like the most natural thing to do.

We might follow the Canada geese next fall. If my knees can take it.

———————————

Ps:

The above was narrated to me many summers past, by an American – Indian couple, Shankar Ghosh and his second wife, Sally Culver. I had come to know them through Shankar’s son, Prabir, who was my colleague at Pratt and Whitney.

I took the liberty to make it sound like it was Shankar Ghosh speaking instead of them both. Sally’s telling felt so vivid that I guess I wanted to put myself in Shankar’s place and view it as him. What can I say? I am a complicated man.

Both, Shankar and Sally are no more, having succumbed to Covid in 2020.

I envy the characters in your story, Achyut. In their golden years at least they do have each other. 🙂

LikeLike

Wow! I had that same feeling about them, Gary and thank you for stopping by!

LikeLike