Tags

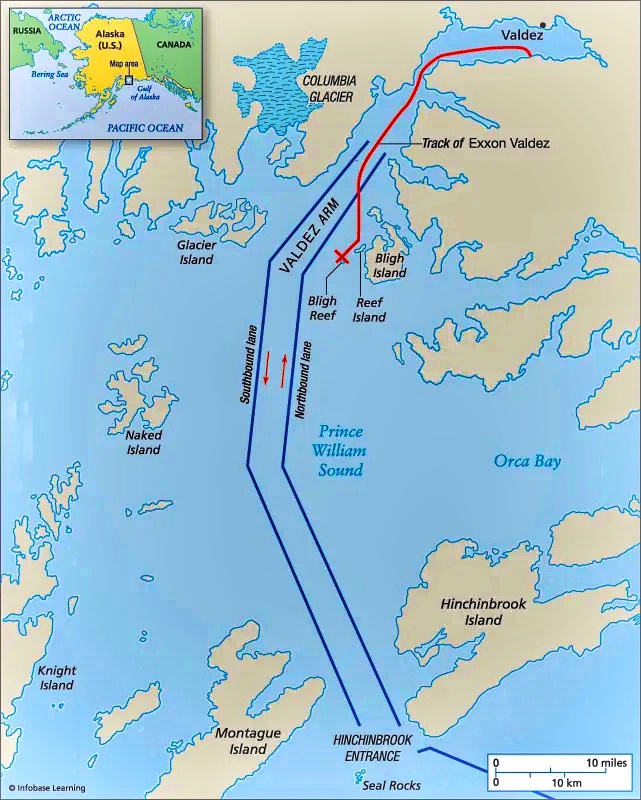

When the Exxon Valdez identified floating ice ahead, it followed procedure. It sought and received clearance to leave the south-bound(west) lane and enter the north-bound(east) lane.

At no time, however, did the vessel report or seek clearance to cross even the inbound lane entirely and deviate further east. Which is exactly what the tanker did.

Three hours after departing the oil terminal, the Exxon Valdez cut right through the inbound lane and headed straight for Bligh Island Reef, where it ran aground, tearing a large ugly gash in the hull below the waterline and rupturing 8 of it’s 11 tanks.

The tanker came to rest facing roughly southwest, its hull stuck on a sharp pinnacle of Bligh Reef. At the time, it was fully loaded, with 53 million gallons of crude. Within the first three hours, 5.8 million gallons had gushed out of the tanker.

The nightmare had begun.

Until the Exxon Valdez piled onto Bligh Reef, the system designed to carry 2 million barrels of North Slope oil to West Coast and Gulf Coast markets daily had worked perfectly, perhaps too well. At least partly because of the success of the Valdez tanker trade, a general complacency had come to permeate the operation and oversight of the entire system. That complacency was shattered when the Exxon Valdez ran aground.

No human lives were lost as a direct result of the disaster, though four deaths were associated with the cleanup effort that followed. Indirectly, however, the human and natural losses were immeasurable – to fisheries, subsistence livelihoods, tourism and wildlife.

The most concerning loss was the sense that something sacred in the environmentally unspoiled landscape of Prince William Sound and the waters of Alaska had been defiled.

——————————-

When disaster struck, Hazelwood had been below deck, leaving the Third Mate, Gregory Cousins, at the helm. There are reports that the presence of a comely female lookout on the bridge distracted Cousins, who had been trying to get into her pants from the very start of the voyage.

Capt. Hazelwood felt a sudden shudder and rushed to the bridge as the ship came to rest, pierced through, like a grotesque kabob on a shiek. Third Mate, Cousins, had immediately throttled the tanker down to idling.

In an effort to dislodge the vessel from the rock, the captain ordered the engine back on and “full ahead”, simultaneously issuing a series of rudder commands, not knowing the extent of the damage fully and apparently not aware how close he was, to tearing the tanker apart from the stress generated by the full throttle.

If the tanker had broken apart and sunk, the crew wouldn’t last even a minute in the icy waters of the sound. Nonetheless, Hazelwood kept the engine running until 1:41 a.m., when he finally abandoned efforts to get the vessel off the reef.

This super tanker had a schmuck in charge.

By the time the oil had stopped flowing, nearly 11 million gallons had leaked out, contaminating 1,300 miles of shoreline and stretching over 470 miles from the crash site. A combination of Bligh Reef’s remote location (accessible only by boat or helicopter) and a lack of preparedness – by way of oil skimming equipment and effective chemical dispersants – made a speedy response difficult.

At its peak, the clean-up effort involved more than 11,000 people and 1,000 vessels. Workers skimmed oil from the ocean’s surface and had to hose down goo-covered birds staggering around on the beaches.

————————————

In the immediate aftermath, the town of Valdez took on the look of a boom town, swelling to eight times its normal size by the summer of 1989, as hundreds of clean-up crew and volunteers poured in.

The skipper of the Exxon Valdez, Capt. Joe Hazelwood, was eventually acquitted of felony criminal negligence by an Alaska jury despite evidence of alcohol in his bloodstream at the time of the accident.

In a civil case, Exxon was hit with a $5 billion civil judgment for its role in the accident. For Exxon, the amount was piddly and yet, the suit was later settled in 1991 for a mere $900 million with the active connivance of a bunch of corrupt Alaska lawmakers and a business-friendly US Supreme Court that was on the take from big business long before Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas came along and showed the world how corrupt the US Supreme Court really is.

$900 million was chump change for a company with an annual revenue of $130 billion in 1991.

For the Alaskan communities devastated by the spill, the reduced verdict was insulting. In August 1993, feeling cheated after four years of calling for action on addressing the environmental impact, a group of fishermen sailed off to begin a blockade of the 800-metre wide neck of the inlet, the Valdez Narrows, which all tankers must pass through.

The US Federal Government was left with no alternative but to step in quick. The blockade was called off after Clinton’s Interior Secretary, Bruce Babbit, promised to release $5 million of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill restoration funds for studies of the effects of the spill on the ecosystem around Prince William Sound, which began in the following year.

The Valdez Oil Terminal has 18 oil storage tanks capable of holding 7.2 million barrels of crude at any given time. That would be the equivalent of around 5 supertanker-loads, or in other words two-three days of normal terminal operations. The blockade lasted three days and kept seven tankers waiting, while the Alyeska Pipeline continued to pump the oil into the terminal, bringing the enormous portside storage tanks perilously close to overflow levels.

——————————-

Exactly 35 years on, Prince William Sound has regained its pristine beauty. Crystal blue waters have once again replaced the thick black goo.

Geologists have reported the burgeoning of new flora and fauna that take one’s breath away. It is as if nothing ever happened. Fisheries are booming and in summer, thousands of tourists rush in to watch those magnificent whales leap straight out of the water as if they were circus artists, paid to put on a show.

As for the oil, more of it is being loaded on tankers today at the Valdez Terminal than ever before. From one berth handling a single tanker and a turnaround time of two days, now two berths handle a tanker each in a turnaround time of one day, a 400% increase in traffic.

————————————-

In the immediate aftermath of any event, there will always be some winners. The Exxon Valdez oil spill had a few and they were the hotel and Bed & Breakfast owners, fully booked with 39000 out-of-towners. Now after three decades, those accommodations have expanded and the town teems with Holiday-Inns and Best Westerns and feels more like a resort town than an oil terminal.

On the face of it, in the long term everybody, including the eco-system, appears to have won.

How long will Prince William Sound hold onto its win?